Ipl Laser For Port Wine Stain>A port wine stain is an irreversible skin discoloration, as anyone who has seen one will attest. Hemangiomas and capillary malformations, the two most common causes of port wine stains, are collections of tiny blood vessels. Laser therapy may be effective in removing the discolouration in certain patients.

In laser therapy, a concentrated beam of light is used to kill off the cells in a specific location. Although the precise mechanism is not fully understood, it is thought that the cells are damaged by the laser’s heat and eventually die. In order to remove all of the diseased tissue, this treatment may require multiple sessions.

One of the most prevalent kinds of birthmarks, port wine stains can occur anywhere on the body. Various treatment modalities have developed over time, with some being relatively straightforward and successful and others being more involved and less fruitful. You should be aware that laser therapy for port wine stains is now a possibility, and that this applies to both minor and large stains. Read on to learn more on ipl laser for port wine stain/port wine stain after laser treatment.

Ipl Laser For Port Wine Stain

A birthmark is a spot on the skin that is either present at birth or appears shortly after that. There are two main types: pigmented and red birthmarks. Pigmented birthmarks are dark and include moles and café-au-lait spots. Red birthmarks involve the blood vessels, owing their color to blood. Port-wine stains and hemangiomas are examples of red birthmarks.

What are hemangiomas and port-wine stains?

A hemangioma is a small vascular tumor that is generally both harmless and painless. The strawberry hemangioma is also called a strawberry mark or hemangioma simplex. It can appear anywhere on the body, but is most common on the face, scalp, back or chest. A strawberry hemangioma is made up of small blood vessels packed together that grow rapidly at first and then stabilize at a fixed size until disappearing, usually before the child is ten years old. It may leave behind slightly puckered or discolored skin.

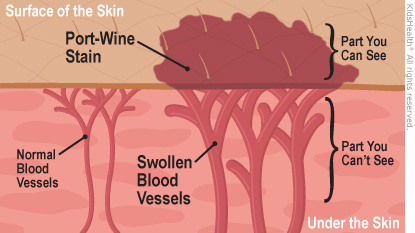

Port-wine stains are the red birthmarks most likely to need treatment since they don’t fade away as the child gets older. They are permanent, likely to appear on the face. Port-wine stains vary in size and are flat birthmarks composed of dilated capillaries, taking on a red or purple hue.

Do red birthmarks need treatment?

Most red birthmarks are harmless. They should be treated, however, if they large, disfiguring, or near the eye. They should also be removed if they make the child self-conscious.

What is IPL therapy?

IPL treatment therapy is a kind of laser therapy used to treat abnormally red skin, like that seen in rosacea or red birthmarks. The acronym stands for Intense Pulsed Light. Unlike conventional lasers, IPL uses several different wavelengths of light, not just one. A machine sends light energy into the target cells and heats them up and thus damages the cells. An advantage of IPL therapy is that it can be used to treat the lower layers of the skin without affecting or damaging the upper layers.

What does IPL therapy involve?

The patient will have to stay out of the sun for several weeks before and after the treatment. During the treatment, a topical anesthetic may be applied to the treatment site. Then, a cool gel is added to the site, and protective eyewear is provided to the patient. The glass surface of the IPL laser machine’s treatment makes contact with the skin to deliver pulses of light to the birthmark.

A treatment session typically takes 20 minutes, and the patient can immediately leave and go about their business afterward. The patient will usually need 4 or more sessions every 3 to 6 weeks to get the desired results.

Are there any side effects?

The patient may experience the symptoms of a mild sunburn-like redness and peel for a few days after the treatment. Blisters occur in a few rare cases.

Port Wine Stain After Laser Treatment

avoid rubbing or scratching the area. Gently clean it with lukewarm water and follow your doctor’s instructions for care of the treated area. Usually, this means putting an antibiotic ointment on it for the first few days, followed by moisturizing.

A port-wine stain is a type of birthmark. It got its name because it looks like maroon wine was spilled or splashed on the skin. Though they often start out looking pink at birth, port-wine stains tend to become darker (usually reddish-purple or dark red) as kids grow.

Port-wine stains won’t go away on their own, but they can be treated. Laser therapies can make many port-wine stains much less noticeable by shrinking the blood vessels in the birthmark and fading it.

What Are the Signs of Port-Wine Stains?

Port-wine stains (also known as nevus flammeus) can be anywhere on the body, but most commonly are on the face, neck, scalp, arms, or legs. They can be any size, and usually grow in proportion as a child grows.

They often change in texture over time too. Early on, they’re smooth and flat, but they may thicken and feel like pebbles under the skin during adulthood.

What Challenges Can Happen With Port-Wine Stains?

For most kids, port-wine stains are no big deal — they’re just part of who they are. And some port-wine stains are barely noticeable, especially when they’re not on the face.

But port-wine stains often get darker and can sometimes become disfiguring and embarrassing for children. Port-wine stains (especially on the face) can make kids feel self-conscious, particularly during the already challenging preteen and teen years, when kids are often more interested in blending in than standing out.

Can Port-Wine Stains Be Prevented?

Port-wine stains can’t be prevented. They’re not caused by anything a mother did during pregnancy. They may be part of a genetic syndrome, but more often are simply “sporadic,” meaning they are not genetically inherited or passed on.

How Are Port-Wine Stains Diagnosed?

Doctors can sometimes tell if it’s a port-wine stain by looking at a child’s skin. Port-wine stains usually are nothing more than a harmless birthmark and don’t cause problems or pain. Rarely, though, they’re a sign of other medical conditions.

For example, doctors will monitor port-wine stains on or near the eye or on the forehead. That’s because they may be linked to a rare neurological disorder called Sturge-Weber syndrome that causes problems like seizures, developmental delays, and learning disabilities. Stains on the eyelids may also lead to glaucoma — increased pressure inside the eye that can affect vision and lead to blindness if it’s not treated.

If there’s a concern about the location of a port-wine stain or symptoms, doctors may order tests (such as eye tests or imaging tests like an X-ray, CT scan, or MRI) to see what’s going on and rule out another problem. If a child has a port wine stain anywhere on the body, it’s important for a specialist to examine it to see what type it is and what kind of monitoring and treatment it needs, if any.

How Are Port-Wine Stains Treated?

Some port-wine stains are small and hard to see. But others can be upsetting for kids, especially if they’re large, dark, or on the face. And any birthmark can take a toll on a child’s self-confidence, no matter how large or small the mark might be.

The good news is that lasers (highly concentrated light energy) can make many port-wine stains much lighter, especially when the birthmark is on the head or neck. Dermatologists or plastic surgeons usually give several treatments with a “pulsed-dye” laser. The laser targets the pigmentation in the stain and fades it. Multiple treatments can make the birthmark fade quite a lot.

Laser treatment often starts in infancy when the stain and the blood vessels are smaller and the birthmark is much easier to treat. But laser treatments also can help older kids and teens too. It’s just that the longer someone has had the stain, the harder it might be to successfully treat it.

Laser treatment can be uncomfortable. Kids can usually get an anesthetic as a shot, spray, or ointment to numb the area. Young children and infants will get general anesthesia to help them sleep or relax during the procedure. These treatments are very brief, usually less than 10 minutes. After treatment, the area might be irritated and inflamed at first, similar to a bad sunburn. But it will be back to normal in 7–10 days. Multiple treatments, if needed or desired, can be done as often as every 6–8 weeks.

For port-wine stains that get bumpy, thick, or raised, doctors sometimes need to use another type of laser or surgery. Port-wine stains can also develop grape-like growths of small blood vessels called vascular blebs. Usually, these aren’t cause for concern, but they often bleed and may need to be removed.

In the past, some people chose other treatments, like freezing, tattooing, even radiation. But these aren’t as effective — or as safe — as laser therapy. Laser surgery is the only treatment that works on port-wine stains with less risk of damaging or scarring the skin. Sometimes, laser treatments may make the pigmentation darker than normal, but this usually is just temporary.

Keep in mind that laser treatments may not get rid of the birthmark entirely (though some birthmarks disappear completely after treatment). Plus, over time the birthmark may come back and need to be retreated.

For a few kids, laser treatment might not work at all. Every child’s port-wine stain is different, so how well the treatment works will be different for each child.

How Can Parents Help?

Port-wine stains can get very dry sometimes, so it’s important to use a moisturizer on the affected skin. Call the doctor if your child’s port-wine stain ever bleeds, hurts, itches, or gets infected. Like any injury where there is bleeding, clean the wound with soap and water and, using a gauze bandage, place firm pressure on the area until the bleeding stops. If the bleeding doesn’t stop, call the doctor.

If your child’s port-wine stain was treated with laser surgery, avoid rubbing or scratching the area. Gently clean it with lukewarm water and follow your doctor’s instructions for care of the treated area. Usually, this means putting an antibiotic ointment on it for the first few days, followed by moisturizing.

What Else Should I Know About Port-Wine Stains?

As with any birthmark, port-wine stains (especially on the face) can make kids feel different and insecure about how they look. If it’s clearly visible, people might ask questions or stare, which can feel rude. Even at a young age, kids watch how their parents respond to these situations and take cues about how to cope with others’ reactions.

Practice responses so your child will feel more prepared when asked about it. It can help to have a simple, calm explanation ready like, “It’s just a birthmark. I was born with it.”

Talking simply and openly about a birthmark with kids makes them more likely to accept it as just another part of themselves — like their height or eye color. Of course, it’s still natural if kids want to minimize a birthmark. Besides laser treatments, special cover-up makeup can help hide the stain.

It helps kids emotionally to be around supportive family and friends who treat them like everyone else. Work with teachers and school staff to ensure your child has a supportive learning environment free from bullying.

Kids with port-wine stains (or any birthmark, really) need to know that they’re no different from other kids. It may help to tell your child that kids born with a port-wine stain are unique in a good way — it’s a special, colorful part of themselves that few other people have.

Importance Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common skin disorder of follicular prominence and erythema that typically affects the proximal extremities, can be disfiguring, and is often resistant to treatment. Shorter-wavelength vascular lasers have been used to reduce the associated erythema but not the textural irregularity.

Objective To determine whether the longer-wavelength 810-nm diode laser may be effective for treatment of KP, particularly the associated skin roughness/bumpiness and textural irregularity.

Design, Setting, and Participants We performed a split-body, rater-blinded, parallel-group, balanced (1:1), placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial at a dermatology outpatient practice of an urban academic medical center from March 1 to October 1, 2011. We included all patients diagnosed as having KP on both arms and Fitzpatrick skin types I through III. Of the 26 patients who underwent screening, 23 met our enrollment criteria. Of these, 18 patients completed the study, 3 were lost to or unavailable for follow-up, and 2 withdrew owing to inflammatory hyperpigmentation after the laser treatment.

Interventions Patients were randomized to receive laser treatment on the right or left arm. Each patient received treatment with the 810-nm pulsed diode laser to the arm randomized to be the treatment site. Treatments were repeated twice, for a total of 3 treatment visits spaced 4 to 5 weeks apart.

Main Outcomes and Measures The primary outcome measure was the difference in disease severity score, including redness and roughness/bumpiness, with each graded on a scale of 0 (least severe) to 3 (most severe), between the treated and control sites. Two blinded dermatologists rated the sites at 12 weeks after the initial visit.

Results At follow-up, the median redness score reported by the 2 blinded raters for the treatment and control sides was 2.0 (interquartile range [IQR], 1-2; P = .11). The median roughness/bumpiness score was 1.0 (IQR, 1-2) for the treatment sides and 2.0 (IQR, 1-2) for the control sides, a difference of 1 (P = .004). The median overall score combining erythema and roughness/bumpiness was 3.0 (IQR, 2-4) for the treatment sides and 4.0 (IQR, 3-5) for the control sides, a difference of 1 (P = .005).

Conclusions and Relevance Three treatments with the 810-nm diode laser may induce significant improvements in skin texture and roughness/bumpiness in KP patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I through III, but baseline erythema is not improved. Complete treatment of erythema and texture in KP may require diode laser treatment combined with other laser or medical modalities that address redness.

Trial Registration clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01281644

Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common hereditary, benign disorder of unknown etiology1 that is frequently seen in conjunction with atopy. The hereditary pattern of this skin disorder is thought to be autosomal dominant without a known predisposition based on race or sex.2 Keratinaceous plugging of follicles results in markedly visible papules, often involving the lateral and extensor aspects of the proximal extremities but sometimes also the face, buttocks, and trunk.3 Perifollicular erythema is routinely notable.4 Topical treatments for KP include emollients, exfoliants, and anti-inflammatory agents, such as urea, salicylic acid, lactic acid, topical corticosteroids, topical retinoids, and cholecalciferol. Because most patients obtain limited benefit from these treatments, less conventional treatments, including phototherapy and lasers, have been explored. Among lasers, the 532-, 585-, and 595-nm vascular devices have been used with modest success, particularly in reducing redness.5–8 Longer-wavelength lasers have not been studied for the treatment of KP, and lasers have not been shown to be successful for treating the textural components of KP. Our study investigates the effectiveness of the longer-wavelength 810-nm diode laser for color and texture of upper extremity KP.

We performed a split-body, parallel-group, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial with an allocation ratio of 1:1 and a block size of 2 at an urban academic medical center. The unit of randomization was the individual unilateral upper extremity. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Northwestern University. All participants provided written informed consent.

Patients were recruited from a dermatology practice at Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, and the surrounding community. Inclusion criteria consisted of age 18 to 65 years, good health, Fitzpatrick skin types I to III, and a diagnosis of KP on both upper extremities. We excluded patients who had received any laser therapy to the arms in the 12 months before recruitment, with a concurrent diagnosis of another skin condition or malignant neoplasm, with a tan or sunburn over the upper arms in the month before recruitment, with open ulcers or infections at any skin site, or who were using topical or oral photosensitizing medications.

When potential participants called or e-mailed the clinic for possible inclusion in the study, they underwent prescreening (performed by O.I.) over the telephone using the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Once enrollment criteria were met, patients were scheduled for a total of 4 visits, 4 to 5 weeks apart, in the Department of Dermatology, Feinberg School of Medicine.

On the patient’s first visit, one of us (O.I.) reviewed the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After the patients provided written informed consent, they separately rated redness and roughness/bumpiness on each arm using a scale of 0 (least severe) to 3 (most severe) for a total maximum score of 6 per patient per arm. Next, patients were randomized into 2 groups as described below, and baseline standardized digital photographs were obtained. Each patient received treatment using the 810-nm pulsed diode laser to the arm randomized to be the treatment site. After laser treatment, both sides were treated with topical petrolatum. Treatments were repeated twice for a total of 3 treatment visits, with visits spaced 4 to 5 weeks apart. At the fourth and final visit, 12 to 15 weeks after the initial visit, the patients again rated disease severity as previously described. At this last visit, 2 blinded dermatologists (S.Y. and M.A.) also rated the roughness/bumpiness and redness of the treatment and control arms separately using the same scales, and digital photographs were again obtained.

Patient screening and enrollment were performed by one of us (M.D.), as were random sequence generation and concealment (R.K.), which were conducted by coin toss of the same fair coin, with the outcomes (1 or 2) recorded separately on individual paper cards then placed in sealed, opaque, consecutively numbered envelopes. Each patient was assigned to one of 2 groups (by W.D.). Patients in group 1 were designated to receive laser therapy on the right arm, and those in group 2 were assigned to receive laser therapy on the left arm. All study treatments were delivered by the same clinician (D.B.).

All study treatments used the 810-nm pulsed diode laser. A lidocaine and prilocaine–based cream was applied to the arms 30 to 60 minutes before treatment and washed off before treatment. Laser therapy was performed on the treatment side at a fluence of 45 to 60 J/cm2 (to convert to gray, multiply by 1) (depending on Fitzpatrick skin type) and a pulse duration of 30 to 100 milliseconds, with precise settings selected to be just below the patient’s threshold for purpura. Each treatment session entailed 2 nonoverlapping passes separated by a 1-minute delay. The patient was then instructed to minimize sun exposure and apply sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 50 to the treatment area daily until the next visit.

The primary outcome measure was the difference in disease severity score, including redness and roughness/bumpiness, between the treated site and the control site as rated by the blinded dermatologists at 12 weeks after the initial visit. This scale was not validated because no relevant validated scale was available. However, raters were trained on the use of the study scale, and before the review of study images, they were asked to rate archival skin images on the same 4-point qualitative subscales used in the study. Raters reviewed and rated archival images separately and then reconciled their ratings through face-to-face forced agreement, with the process repeated until concordance was achieved between raters and their separately rated scores were consistently equivalent.

During the evaluation of study data, forced agreement was used to reconcile blinded ratings. The secondary outcome measure was the change from baseline in disease severity of each arm as rated by the patients.

Power Analysis and Sample Size

Assuming an SD of change of 0.84, a sample of 20 patients had 80% power to detect median differences (or median changes) in severity scores of 0.5. We assumed a 2-sided test and type I error rate of 5%.

We used the Wilcoxon signed rank test to compare the magnitude of change from baseline between treatment and control for all patient ratings (redness, roughness/bumpiness, and overall score). Blinded dermatologists’ ratings of the treatment and control sides were also compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Patient Baseline Demographic Characteristics

The study was conducted during a 7-month period from March 1 to October 1, 2011. A total of 26 patients underwent screening for our study, and 23 of those patients (46 arms) met our criteria and were enrolled in the study. Of these 23 patients, 18 (36 arms) completed the study and underwent analysis, 3 were lost to or unavailable for follow-up, and 2 voluntarily withdrew owing to inflammatory hyperpigmentation after the laser treatment. The demographic characteristics of our patients are presented in the Table. At baseline, patients rated the severity of the roughness/bumpiness in the texture of their arm test sites at a median score of 1.5 (interquarile range [IQR], 1-2) and the severity of the erythema of their arm test sites at a median score of 2.0 (IQR, 1-2). (The maximum score for both ratings was 3.0.)

At follow-up, the median redness score assigned by the blinded raters for the treatment and control sides was 2.0 (IQR, 1-2), a null difference (Figure 1). The median roughness/bumpiness score was 1.0 (IQR, 1-2) for the treatment sides and 2.0 (IQR, 1-2) for the control sides, a difference of 1 (P = .004) (Figure 1). The median overall score combining erythema and roughness/bumpiness was 3.0 (IQR, 2-4) for the treatment sides and 4.0 (IQR, 3-5) for the control sides, a difference of 1 (P = .005) (Figure 1).

Patient Self-assessment Scores

At follow-up, patients’ self-reported median erythema rating for the control sides did not change from the baseline score of 2.0 (IQR, 1-2), but the self-reported median erythema score for the treatment side decreased from 2.0 to 1.5 (IQR, 1-2), a nominal difference that was not statistically significant (P = .13) (Figure 2). The median roughness/bumpiness score for the control sides increased from 1.5 to 2.0 (IQR, 1-2) and for the treatment sides decreased from 1.5 to 1.0 (IQR, 1-2). The 1-point decrease in roughness/bumpiness in the treatment arm compared with the control arm was significant (P = .008) (Figure 2). The overall score (erythema and roughness/bumpiness) for the control sides increased from 3.5 to 4.0 (IQR, 3-4), and for the treatment arm decreased from 3.5 to 2.5 (IQR, 2-4), with the cumulative difference of 1.5 points being significant (P = .005) (Figure 2).

We found no unexpected adverse events associated with laser treatment. Two participants developed inflammatory hyperpigmentation after laser treatment and chose to withdraw from the study. These patients were instructed to continue sun-protective measures to their affected extremities, and in both cases hyperpigmentation completely resolved within 3 months.

We investigated the effectiveness of the 810-nm diode laser in the treatment of KP. After 3 treatments spaced 4 to 5 weeks apart, blinded dermatologist ratings and patient self-report indicated significant improvements in skin texture and roughness/bumpiness when compared with baseline However, neither raters nor patients detected a significant change in erythema.

Most topical treatments for KP, including emollients, corticosteroids, and retinoids, are of limited effectiveness.9 Light-based treatments have typically entailed use of vascular lasers, like the application of a 532-nm potassium titanyl phosphate laser to treat a case of resistant facial KP by Dawn et al.5 Repeated treatments resulted in a marked improvement in erythema and some clearance of papules. A study of 12 patients using the 585-nm pulsed-dye laser6 found improvement in erythema but not in roughness/bumpiness. A similar report7 described a case in which multiple treatments with a 595-nm pulsed-dye laser induced marked improvements in facial erythema, patient satisfaction, and quality of life. A study of 10 patients treated with a 595-nm pulsed-dye laser8 confirmed these results.

To our knowledge, our study is the first of its kind to investigate the use of a longer-wavelength laser, the diode laser, in the treatment of KP. More important, our results are the first from a clinical trial that demonstrate the effectiveness of laser treatment of the textural abnormality and roughness/bumpiness associated with KP. The data from our investigation suggest that the 810-nm diode laser is a particularly promising and effective treatment for the nonerythematous variants of KP. The variant of KP known as keratosis pilaris alba, which presents mostly as follicular papules, may be highly responsive to this laser modality.10 The variant that includes perifollicular erythema with follicular papules, keratosis pilaris rubra,9,10 may best respond to joint treatment with diode and vascular lasers, with the former improving texture and the latter addressing erythema.

We have theoretical reasons for selecting the 810-nm diode laser and the settings used in this study. Specifically, KP is an inflammatory condition of vellus hair follicles. Compared with terminal hair, vellus hair is relatively deficient in melanin (ie, has less chromophore) and smaller in diameter (ie, has shorter thermal relaxation time). Based on the theory of selective photothermolysis, these features would be consistent with a thermal relaxation time of approximately 50 milliseconds, which means that a pulse duration of less than 50 milliseconds, such as the 30 milliseconds used in this study, would be appropriate for treatment. Because of a substantial lack of chromophore, the fluence required for photothermal destruction of a vellus hair follicle is 40 to 45 J/cm2, greater than that for a terminal hair. Ideally a highly absorbing wavelength such as 695 nm would be the best to treat vellus follicles, but this wavelength is absorbed by epidermal pigment in darker skinned individuals before it can reach deeper targets, such as the stem cells in the bulge region of the follicles. Similarly, 1064 nm is not highly selective for melanin, and we know that the vellus follicle has little melanin to begin with. As a consequence, the 810-nm wavelength appears to be the best choice because its depth of penetration is sufficient, it has selectivity for melanin, and it is compatible with a pulse duration of 30 milliseconds.

In terms of adverse events, our study found that treatment with the 810-nm diode laser was safe and not associated with any serious or unexpected adverse events. Although 2 patients (9%) developed bothersome inflammatory hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, resulting in their withdrawal from the study, these sequelae resolved completely in the medium term. Further counseling about the need for sun protection and avoidance of tanning during the period of laser treatment may mitigate the risk for posttreatment inflammatory hyperpigmentation in the future.

A limitation of our study is that enrollment was restricted to participants with Fitzpatrick skin types I to III. The exclusion of darker skin types was not incidental but rather designed to minimize the risk for posttreatment inflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is more common after laser procedures in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. That posttreatment inflammatory hyperpigmentation was observed in this study despite careful patient selection suggests that this precaution was appropriate. Regardless, patients with darker skin types can indeed be treated safely with the diode laser if gentle settings are used. Once this treatment paradigm is optimized, such broader application will likely be appropriate and feasible. One protective benefit of the current treatment settings was that they were deliberately below the threshold for purpura and thus designed to avoid bruising, which can resolve with tan pigmentation, particularly in darker skin. To the extent that the 810-nm diode laser has hair-removing activity, this treatment may be inappropriate for patients who do not want hair loss at the site of their KP. Finally, although incidental reports from some participants previously in this study have indicated that they have maintained textural benefits for more than a year, it remains to be seen to what extent these improvements are maintained over the longer term. To the extent that laser treatment may significantly modify hair growth in abnormal vellus hair follicles initially induced by genetic predisposition, improvement may be long lasting. This result would then be parallel to the case of traditional hair removal, in which posttreatment long-term remission of coarse terminal hairs and the corresponding pseudofolliculitis is often observed.

However, this study was not designed to assess long-term improvement, and additional studies would need to be performed to systematically measure the duration and likelihood of persistent benefits. The present study only provides proof of concept and indicates that improvement of the textural abnormalities associated with KP is possible after treatment with an 810-nm diode laser.

By objective and subjective measures, we found that, among lighter-skinned persons, serial treatment with a long-pulsed 810-nm diode laser at subpurpuric levels provided medium-term improvement in KP, particularly for the associated roughness/bumpiness and textural irregularity. Combined with preexisting data about the utility of vascular lasers for the reduction of KP-associated erythema, this finding suggests that laser treatment may comprehensively address the clinical manifestations of KP in selected patients. Future studies may assess the durability of these responses and the comparative effectiveness of different long-wavelength lasers.

Ipl Laser For Port Wine Stain

A port-wine stain, or nevus flammeus, is a dark red or reddish-purple birthmark that really does look as if someone spilled wine on the patient’s skin. Port-wine stains can occur anywhere, but they are most commonly found on the face, scalp, neck, legs, or arms. If you have been looking for an effective treatment for this condition, then it is a good idea to learn more about IPL therapy.

What Causes Port-Wine Stains?

Port-wine stains are vascular birthmarks. They develop on patches of skin that don’t have enough nerve fibers to keep the capillaries narrow. The capillaries thus keep expanding, so more blood than usual flows into them and form the stain under the skin. There is no way to prevent port-wine stains from developing.

Are They Dangerous?

Port-wine stains are generally harmless, but they can be disfiguring, especially if they’re large and/or on the face. If a port-wine stain is on the forehead or near the eye, the doctor will want to monitor the child, for the stain could be associated with an uncommon neurological disorder called Sturge-Weber syndrome. Port-wine stains on the eyelids may increase the chances of developing glaucoma.

What is IPL?

IPL, which stands for “intense pulsed light,” is a treatment that uses short bursts of highly intense polychromatic light. A laser, by contrast, consists of coherent light of a single wavelength. The IPL penetrates just below the skin’s surface and causes the dilated blood vessels to heat up. The capillaries collapse and eventually disintegrate, causing the stain to fade.

What Happens During a Treatment?

During the procedure, the patient will see brief flashes of light and feel momentary pulses of heat. The treatment will typically take only 15 to 20 minutes. Most people need around three treatments, with each one being six to eight weeks apart.

Who is a Good Candidate for IPL Treatments?

The best candidates for IPL therapy are people who are sick and tired of the appearance of their port-wine stains on their bodies. IPL can also be used to treat rosacea, age spots, wrinkles, vascular lesions, and much more. The treatment is extremely safe, and there is no downtime involved. Good candidates have overall good health as well as realistic expectations for what the treatment can do.

The skin is the largest organ of the body, so it’s no surprise that skin imperfections, blemishes, marks and lesions can happen. Many skin conditions not harmful to your health, but can be a nuisance, unsightly or even embarrassing. Keratosis Pilaris is one such condition, and treating Keratosis Pilaris is simple.

It’s very common and completely harmless but if you suffer with it, can be something of a less than welcome part of your life, due to its sometimes, unattractive appearance. If you have small pimples on the skin that look like permanent goose bumps on areas of the body such as the back of your arms, legs, bottom and even the back, face, eyebrows and scalp, which sometimes get itchy or red, you may have Keratosis Pilaris.

The condition occurs when there is a build-up of a substance called Keratin, a natural protein, which in fact is the main component of the hair as well as healthy skin. This, excess Keratin blocks the openings of the hair follicles, which can cause the small red or white bumps to appear. Keratosis Pilaris also takes the name of “chicken skin” as the skin takes on this appearance. So, no wonder that many people who experience it would like to reduce oreven, eradicate the symptoms.

So, how are we treating Keratosis Pilaris?

Fortunately, at Skin Perfection London, we offer a choice of non-surgical solutions for treating Keratosis Pilaris, painlessly, safely and effectively, from the comfort of our clinic, which is based in the heart of London, between Oxford Street, Harley Street and Bond Street. Treatments can be used alone or combined, for a holistic approach to reducing the chicken skin appearance.

Laser hair removal is a superb way of treating Keratosis Pilaris at its cause. It’s safe, virtually painless and can be permanent! It works by emitting short pulses of light in to the hair follicle, causing it to stop growing hair and to close. This means that it can no longer be blocked by the Keratin and the condition can be drastically improved. The treatment may take up to 9 sessions for optimum results, but can be a long-term solution to this troublesome condition and far better than having to shave, wax or epilate the hair, which can be extremely painful and can exacerbate the symptoms. Laser hair removal is suitable for all skin types and you could see up to 95% permanent reduction in hair growth, so it’s a win-win!

Medical microdermabrasion could be another option. It works by resurfacing the skin and cleaning blocked and congested pores and offers very little downtime or discomfort. At Skin Perfection London, we use the Derma Genesis medical microdermabrasion system, which utilises tiny medical-grade aluminium oxide crystals, which are swept across the skin by a hand-held device. The crystals are then gently sucked back up, bringing with them dirt, debris and dead surface skin cells. This reveals a smoother, clearer and healthier complexion, less prone to becoming congested. Results can be seen after a course of several sessions and your skin expert will explain the treatment programme, along with expected results, at a no obligation consultation, prior to treatment.

Although a harmless condition, Keratosis Pilaris doesn’t have to be endured and at Skin Perfection London, we make it our mission to offer you the most effective, innovative and high-tech device-led treatments to restore smooth, healthy and sexy looking skin, all-year-round.